The Low-Down on High Flyers

Story and photos by Dave Alexander, Publisher

Drones have been around a while. Argo, the remotely operated deep-sea vehicle that found the Titanic in 1985 is perhaps the first drone to come into our collective knowledge. Images taken by Argo of the infamous cruise liner were breathtaking and provided a stunned planet its first look at the sunken ship in 73 years.

Today’s drones combine high-resolution thermal imaging and overhead high-resolution photos to map fields. The Malheur Experiment Station Summer Farm Festival and Annual Field Day on July 12 featured presentations from two drone experts that are using new technology to predict crop yield and analyze crop health.

Using near-infared cameras and software that uses the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), these drone pilots deliver a thermal map of the fields they have scanned. NDVI is a simple metric which indicates the health of vegetation. When near infrared hits the leaf of a healthy plant, it is reflected back into the atmosphere. As the amount of chlorophyll produced in a plant decreases, less near infrared is reflected. The resulting picture displays healthy, distressed and dead plants in different colors.

Because NDVI determines the level of chlorophyll in plants, the technology can be used for nutrient and disease management. Growers can determine which parts of their fields are underperforming and address those areas before harvest, boosting final yield.

Some growers have been using NDVI images from satellites, but Keil Lampe with Sky Snap in Boise, Idaho, said growers will appreciate the extra resolution provided by drones. Sky Snap’s resolution is an astounding one pixel per 2 inches. Satellites can only manage one pixel per 15 feet. Additionally, satellites can’t scan in clouds, but drones can and results can be provided in 24 hours.

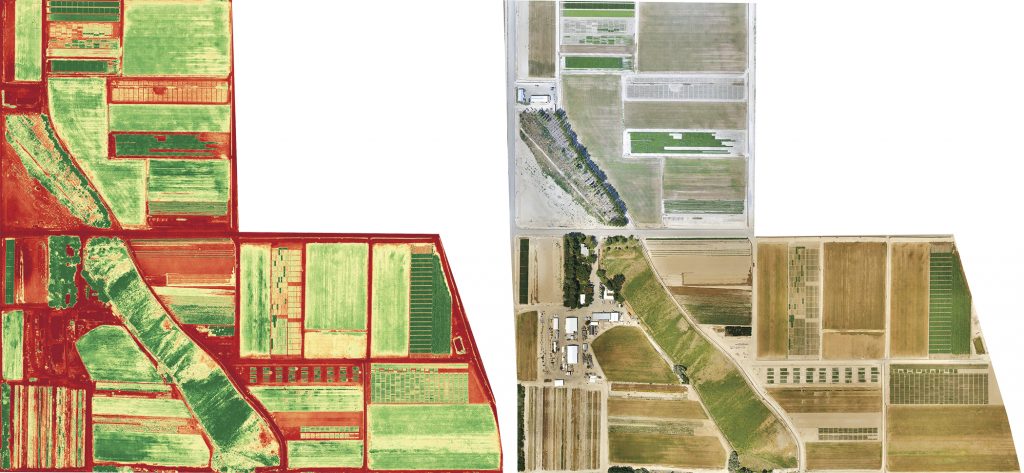

These images, produced by Sky Snap, show the Malheur Experiment Station.

The photo on right is a high-resolution image of the field. The one on left is the NDVI scan. Healthy plants are in medium green.

Bill Ballantyne with Ballantyne Ag Services in Nyssa, Oregon, programs his drones to take photos and NDVI scans in one flight, saving time and money. Ballantyne, a lifelong farmer, said that his images can capture problems before they even show up in scouting. In one case, a grower didn’t believe a scan and two weeks later, the problem did indeed show up. Ballantyne also said his image quality beats satellites, and because satellites are on a fixed schedule, a field scan can be missed at a critical time.

Both Ballantyne and Sky Snap completed fly-overs and scans of the Malheur Experiment Station the week before the field day. Station director Clint Shock said that the final scans matched what he knew was happening in the fields and plants that had been intentionally stressed showed up. Researchers were also able to see things that had gone wrong that they didn’t know about.

Technology evolves. The phone in your pocket has more computing power than Apollo-era computers. Drones working today would no doubt turn Argo green with envy. In the future, drones will deliver what Lampe calls the “complete package,” informing growers what disease is in what plant. While that is something to surely look forward to, drones today are a tool that growers should consider putting in their toolbox.

Clint Shock explains the Sky Snap NDVI scan of the Malheur Experiment Station.