Updates From the Northeastern US

By Lindsy Iglesias and Brian Nault, Cornell University

If you grow onion or other alliums in the northeastern U.S., you might have already heard of a new invasive pest called the allium leafminer (Phytomyza gymnostoma). This tiny fly was first found on a farm in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in December 2015. The fly is originally from Poland, but has become an important pest of alliums throughout Europe and now the northeastern U.S.

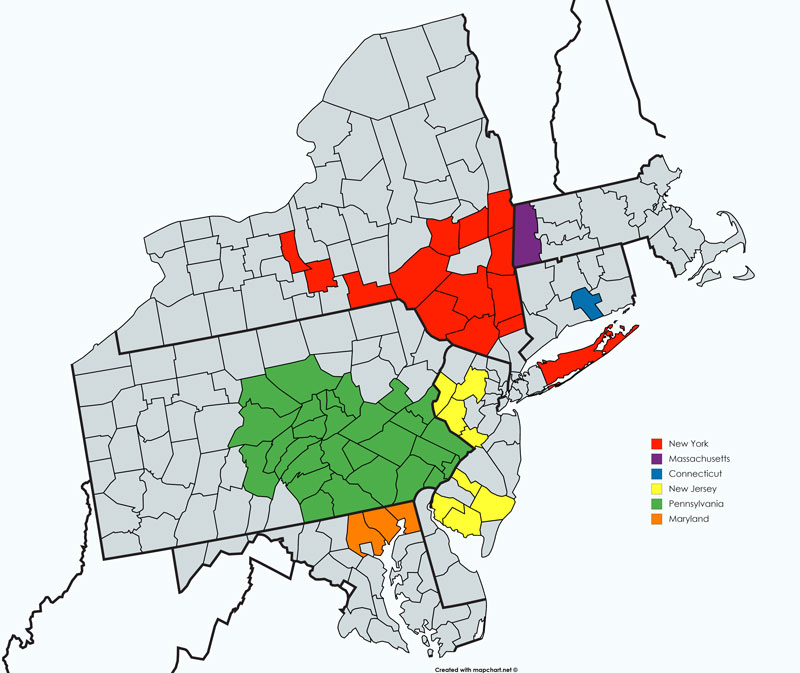

Since 2015, the allium leafminer (ALM) has spread to six states, including Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania (Fig. 1). The mechanism for its spread is unclear, but may be aided by the transport of infested plant material throughout the region. Currently, there are no reports of ALM in other allium growing regions in the U.S.

What to Look For and When

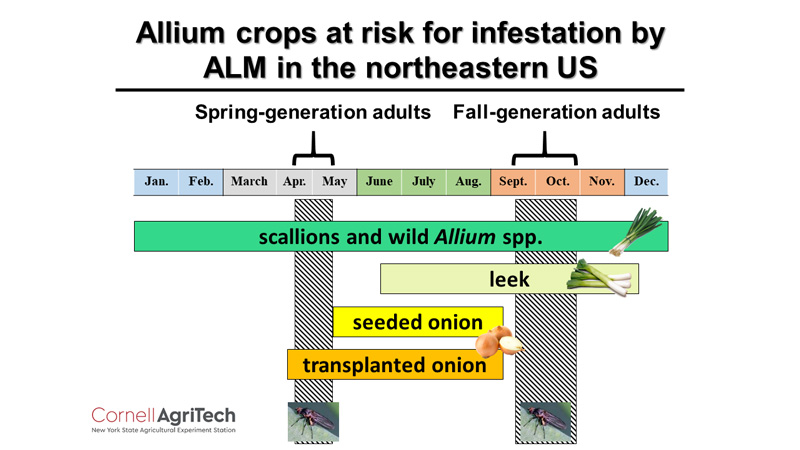

Adult ALM look similar to other leafminer flies found in alliums, such as the American serpentine leafminer (all U.S.) and the vegetable leafminer (southern U.S.). However, ALM is slightly larger than the others (2.5-3.5 mm, Fig. 2). Unlike the other common leafminers, the allium leafminer has two generations a year in the northeastern U.S., one in the spring and one in the fall. Spring-generation adults begin emerging in mid-April, while fall-generation adults begin emerging in mid-September.

Shortly after emerging, the females will search for available alliums to make their distinctive circular punctures, called oviposition marks, on the leaves. These oviposition marks are typically in a linear pattern along the upper half of the leaves and can range from one mark to several (Fig. 3). Females will lay eggs in these oviposition punctures for four to six weeks. Additionally, both males and females can be found feeding on the plant exudates from these marks throughout the season. The oviposition marks are usually the first sign of infestation in a field.

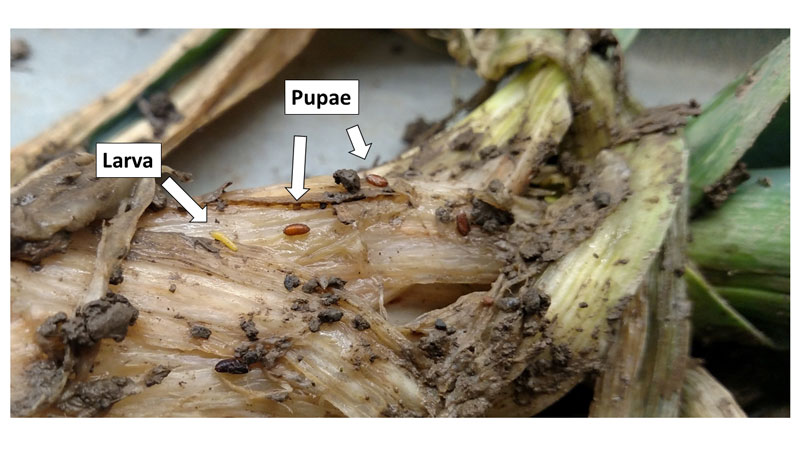

After the eggs hatch, larvae mine through the leaf downward toward the lower portions of the plant (Fig. 3). The larvae are large (approximately 8 mm) compared to other leafminer larvae and are white to light yellow in color (Fig. 4). Larval feeding can occur through early June during the spring generation and late November during the fall generation.

Eventually, the larvae will pupate in the lower portion of the plant or will exit the plant and pupate in the surrounding soil. The pupae are oblong, 3-4 mm long, and range from light to dark brown (Fig. 4). At the end of each generation, the pupae enter a resting stage during the summer and winter months and will remain there until they emerge as adults the following season.

Host Plants, Damage

As the name suggests, the allium leafminer attacks cultivated and wild plants in the Allium genus. The most economically important allium hosts for ALM are dry bulb onion, leek, scallion, chive, garlic and ornamental alliums. Infestation has also been recorded in giant onion, garlic chive, wild garlic and wild onion in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York. The presence of oviposition marks and mining cause cosmetic injury to crops sold for their foliage, such as chive, scallion and ornamentals. The presence of larvae or pupae, larval feeding and associated bacterial rot can render onion, garlic, scallion and leek unmarketable. It is important to note that infestations of ALM in commercial dry bulb onion fields have been negligible and no economic loss has occurred.

The crops that are most at risk for ALM damage are those that have green foliage available during the two generations (Fig. 5). In the northeastern U.S., early-transplanted onions are at risk of infestation in the spring, whereas direct-seeded onion misses both generations completely and should be able to avoid infestation. Scallion and garlic overlap with the spring generation, and scallion and leek are available in the fall; therefore, all are at high risk for attack by ALM. Wild alliums are available during both generations, and though not economically important, can serve as a source of population growth for ALM in the landscape. The worst ALM infestations and most severe economic loss has occurred in leek, scallion and garlic, which were all grown on small farms, especially those managed under organic practices.

What We Know About Management

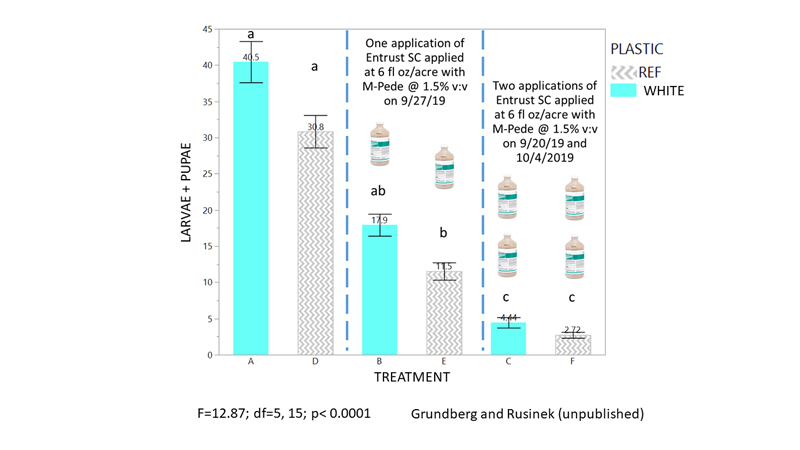

Cultural controls may reduce ALM infestations. Silver reflective mulches have been shown to reduce ALM damage in leeks and scallions by 30 to 35 percent compared to black and white mulches. However, Cornell Cooperative Extension vegetable specialists who conducted the research, Ethan Grundberg and Teresa Rusinek, note that when ALM populations were high, reflective mulches did not completely protect the crop from infestation, and applications of Entrust (spinosad, IRAC 5) were required (Fig. 6).

Additional cultural controls include delaying planting or early harvesting to avoid the spring and fall generations. Delayed planting may be especially useful in the northeastern U.S. to prevent infestation of transplanted onions. Rotating crops out of alliums may also reduce populations by cutting off the food supply during the year.

Sanitation to remove unmarketable plant material that may be infested with ALM larvae or pupae is crucial for controlling populations of flies the following season. Row covers installed before adults emerge at the start of the season and that remain over the crop during the season may help exclude adults from infesting the crop. However, since the first detection of infestation is only after oviposition marks have been made and adult flies are already in the field, timing the installation of row covers to completely protect the crop from egg-laying females will be challenging until better monitoring tools are developed.

Chemical controls are the most effective methods for managing ALM. Always review the product label or contact your local extension agent for more information on the regulations of the product in your state and your crop prior to applying.

Several conventional and OMRI-Listed products have been evaluated as foliar applications for control of allium leafminer in leeks, scallions and onions in New York. The products Scorpion 35SL (dinotefuran, IRAC 4), Exirel (cyantraniliprole, IRAC 28) and Radiant (spinetoram, IRAC 5), all co-applied with LI 700 (soy oil), performed consistently well and provided over 78 percent control of ALM. Of the OMRI products tested, only Entrust (spinosad, IRAC 5) co-applied with M-Pede provided adequate control (70 percent).

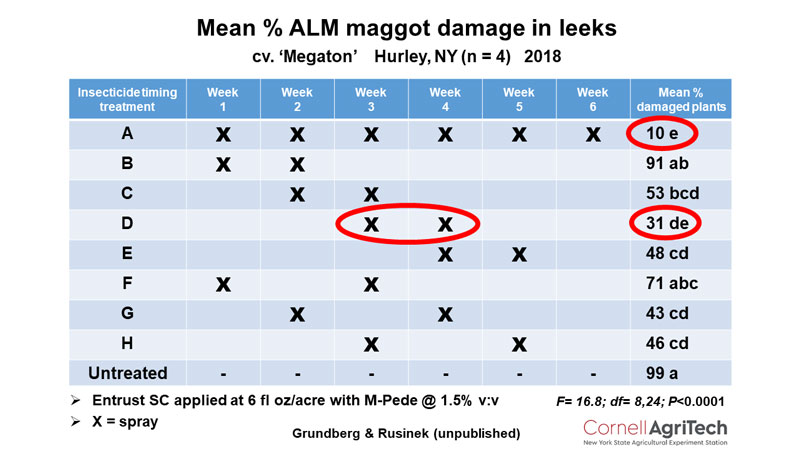

Timing of foliar applications has been investigated to reduce the number of sprays per season in order to meet label restrictions, while still providing adequate control. Trials in leeks in New York evaluated the use of Entrust co-applied with M-Pede at different intervals during the growing season starting when the first oviposition marks were observed in the field. Insecticide programs that had two applications made consecutively in weeks three and four reduced ALM infestation similar to six weekly applications (Fig. 7).

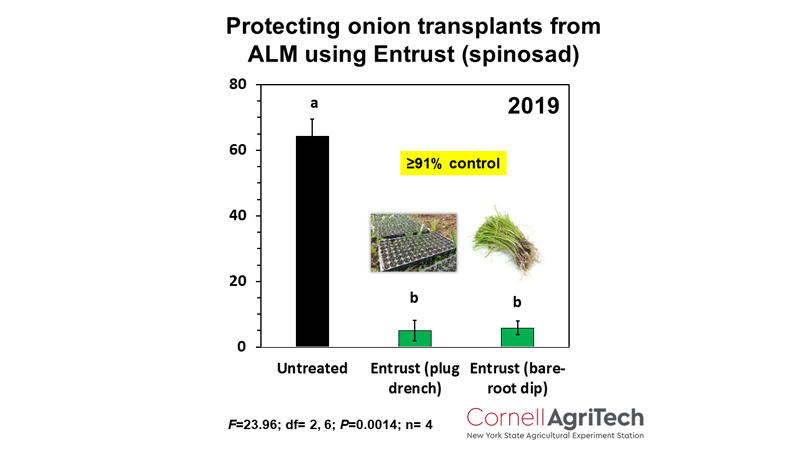

Alternative application techniques have also been evaluated for allium leafminer control in transplanted onions. Entrust has shown to be effective as bare-root dip and plug plant drench treatments, providing more than 91 percent control (Fig. 8). Using Entrust in this manner is not currently on the manufacturer’s label, but is being investigated for future supplementary labels.

What’s Next?

Researchers at Cornell University and Cornell Cooperative Extension are currently trying to understand more about this invasive pest in its new environment. One study has been investigating ALM visual preferences and how this information could be used to inform better trap designs for monitoring. Another study is looking at ALM preferences for different allium crops and how far ALM will travel to find their host in the landscape.

Currently, ALM has not been detected outside of the northeastern U.S. To minimize risk of ALM spreading to other U.S. onion production regions, California has an active quarantine in place for bulb onions produced in states where ALM has been detected. Washington, Oregon, Georgia and Texas are in various stages of the process, but do not have an active quarantine in place yet.

If you think you have seen ALM injury in your allium fields, please contact your local extension agent immediately. Additional questions can be directed to Brian Nault, professor of entomology at Cornell University, at ban6@cornell.edu.