Story by Denise Keller, Editor

Photos by Dave Alexander, Publisher

Through the years, Fagerberg Produce has been shifting more and more of its onion business to the retail market. And years like 2020 – and possibly 2021 – make the Fagerbergs glad to have gone in that direction. The recent increase in demand for onions at retail has shielded Fagerberg Produce from some of the sting that has come with the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the Market

Fagerberg Produce, a grower-shipper in Eaton, Colorado, grows and packs 1,200 acres of onions, with corn and winter wheat grown as rotation crops. The farm’s onion acreage includes yellow, red, white and sweet onions; yellows make up about two-thirds of the crop.

Dave Fagerberg first planted onions in the 1940s. His son Lynn Fagerberg started farming his own onions in the late 1960s and built a packing shed on the farm in the early 1980s. Lynn’s son Ryan Fagerberg joined him 15 years ago. Today, Lynn remains involved in the farming operations, while Ryan runs the processing side of the business, handling sales, pricing and human resources and coordinating production in the warehouse.

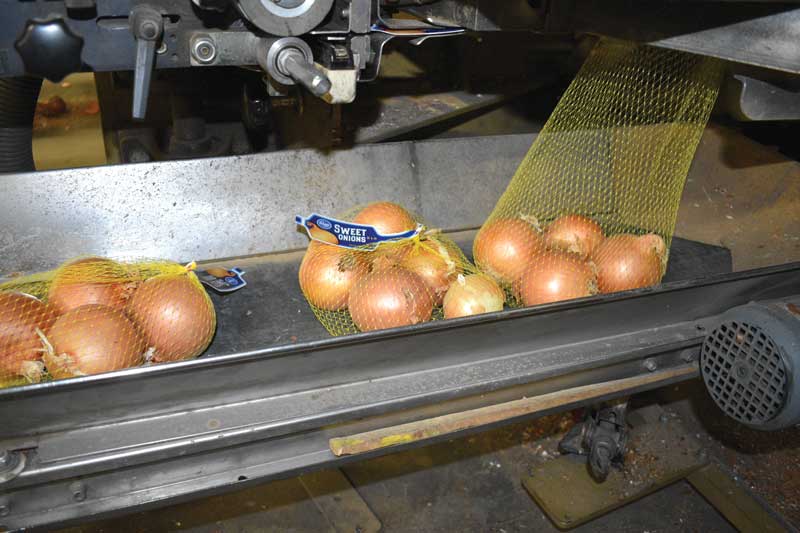

The addition of the packing shed helped the farm’s retail business take off in the 1980s and ‘90s. Since then, the Fagerbergs have been increasingly tailoring the company to meet retail demand rather than foodservice. Currently, 90 percent of the farm’s onions go to retail and 10 percent are sold for foodservice.

Because Fagerberg Produce’s customer base consists mostly of retailers, the company has been fortunate to be somewhat insulated from the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Fagerberg saw a bump in sales around the time of the initial shutdown of restaurants and other non-essential businesses in spring 2020. As consumers started to purchase more onions in grocery stores, retailers began buying whatever onions growers could offer.

“They just needed onions because they would sell out as soon as they would get them,” Ryan Fagerberg says. “It seemed like onions were one of those items that people might have thought were going to be gone all of a sudden. There was definitely an uptick in sales in certain items – produce items and otherwise – and I felt like onions, for whatever reason, were one of those items.”

Although demand has returned closer to normal levels, Fagerberg is glad to be on the retail side of the market.

“It has been a good transition for us. We’re definitely grateful to have that business,” the grower says, adding that the Families to Farmers Food Box program provided another outlet for onions, especially medium yellows.

In the Field

Being a grower-shipper gives Fagerberg Produce its biggest competitive advantage with retailers, Fagerberg says. Customers want to work directly with the farm and value the consistency in product coming from the same farm. They also appreciate having access to information about the quality of the crop in the field and packing shed.

Fagerberg begins planting direct-seeded onions in mid-March and harvests the crop in August through early October. Grown in a 50-mile radius of Eaton in northeastern Colorado, onions generally experience good growing conditions with cool summer nights and little precipitation.

The farm uses sub-surface drip irrigation on 800 acres of onions. Drip lines are installed 8 inches deep and stay in place for 15 to 20 years. The sub-surface drip lines use 40 percent less water, according to Fagerberg, ensuring a quality crop can be grown even during drought conditions. The remainder of the onion acreage is grown under overhead pivot and flood irrigation.

Fagerberg Produce ships its own onion crop August through March and buys and repacks onions from New Mexico, California and Texas in order to supply select customers with year-round onions. A year ago, the company hired Colby Cantwell as a new salesman. Bringing on someone new to the sales desk was a big move for the company, Fagerberg says.

The cost of labor presents the biggest challenge for the company with minimum wage on the rise and the possible elimination of the overtime exemption for agricultural employers looming. Other business challenges include keeping up with various regulations, including new COVID-related rules, and having to change course often to meet moving targets in the areas of food safety and worker safety.

In the Future

Looking ahead, Fagerberg sees the potential of continued opportunity for onions in retail, following the changes brought about by the pandemic.

“I don’t know ultimately what the effect of COVID will be to retailers. Are they going to continue to have increased sales? Maybe. Some people will get used to staying home and cooking at home more. But there are also going to be those people that, once everything is lifted, are probably going to be itching to go out, so they’re going to be less inclined to go to the grocery store. So it will be interesting to see at the end of the day the effect on the onion industry that COVID had,” Fagerberg says.

He plans to monitor trends in the market to see if consumers gravitate toward certain onion packs or if a need arises for more consumer packages as a result of shoppers perceiving them to be safer than bulk onions.

As for production on the farm, Fagerberg has no plans to increase acreage from what it’s been for the last 12 or so years.

“I feel like it’s at a level to where I don’t want to just grow as much as we can or sell as much as we can. I’d rather do it right and make sure we do it the best we can,” the grower says. “We just want to have good customers and make sure we do a good job for them, and we’re pretty content with that.”

While the future at Fagerberg Produce might not include a production increase, Fagerberg is excited to see what advancements in technology might lie ahead.

“Agriculture seems like an industry that always has a lot of innovation. A lot of things change each year and new things seem to be introduced as far as machinery, so that’s an exciting aspect of it.”