|

Click to listen to this article

|

Can Early-Terminated Allium Trap Crops Reduce White Rot Infestations?

By Gia Khuong Hoang Hua and Jeremiah Dung, Central Oregon Agricultural Research and Extension Center, Oregon State University

Robert Wilson, Agricultural & Natural Resources Intermountain Research & Extension Center, University of California

With limited options to control white rot, researchers continue to investigate alternative management strategies. Recent trials looking at the use of trap crops showed some potential, and with more research, the practice could merit a place in an integrated management program.

Disease Management

White rot is a disease of major importance for onion and garlic producers in the western U.S. The fungus that causes white rot, Sclerotium cepivorum, is a plant pathogen that is restricted to Allium hosts and causes root and bulb decay, ultimately resulting in death of the plant.

Crop rotation is not effective at managing white rot because the pathogen can survive in fields for over 20 years as sclerotia, which serve as the dormant stage of the fungus in the absence of Allium hosts. Additionally, it takes very few sclerotia (as little as one sclerotium per quart of soil) to initiate a white rot epidemic, making it difficult to eradicate the fungus to manageable levels.

Sclerotia of the white rot pathogen germinate in response to volatile sulfur compounds that are released by Allium root exudates, and this aspect of the pathogen’s biology can be exploited for white rot management. Previous studies have demonstrated that certain sulfur compounds can elicit the germination of sclerotia when applied in the absence of an Allium crop and reduce sclerotia levels in soil.

Both synthetic (diallyl disulfide, or DADS) and natural (garlic juice, oil and powder) compounds have been shown to be able to reduce sclerotia levels by over 90 percent in field studies, but there can be challenges to wide-scale adoption of sclerotial germination stimulants in white rot-infested production systems. First, the application of sclerotial germination stimulants must coincide with environmental conditions that are suitable for the pathogen (i.e. temperatures ranging from 50 to 75 degrees Fahrenheit, along with adequate soil moisture), and the time required for adequate reductions in sclerotia can be six months or more. Additionally, the application of some of the more effective stimulants (e.g. DADS or garlic oil) requires specialized fumigation equipment. Unfortunately, commercial sources of DADS, which is the most effective germination stimulant, are no longer available for agricultural use.

Allium Trap Crops

Another way to introduce sclerotial germination stimulants into infested fields could be through the use of an Allium trap or lure crop. In this case, our goal would be to grow an Allium crop to the point of eliciting sclerotial germination, but also to terminate the crop before the pathogen can infect and reproduce on the host.

A series of growth chamber, greenhouse and field experiments were conducted in 2020 and 2021 to identify Allium species that could be used as trap/lure crops, evaluate different termination timings, and determine if fungicides could augment trap crops by limiting host infection and pathogen reproduction.

Our initial results suggested that white, red, sweet or bunching onion could all be used as potential trap/lure crops, as sclerotia counts were significantly reduced in all trap crop treatments when terminated at three and seven weeks post-emergence, and also in the red onion trap crop treatment at 11 weeks post-emergence. However, white rot infections were noted in all four Alliums at seven and 11 weeks post-emergence, and sclerotia counts increased significantly when plants were terminated at 11 weeks post-emergence.

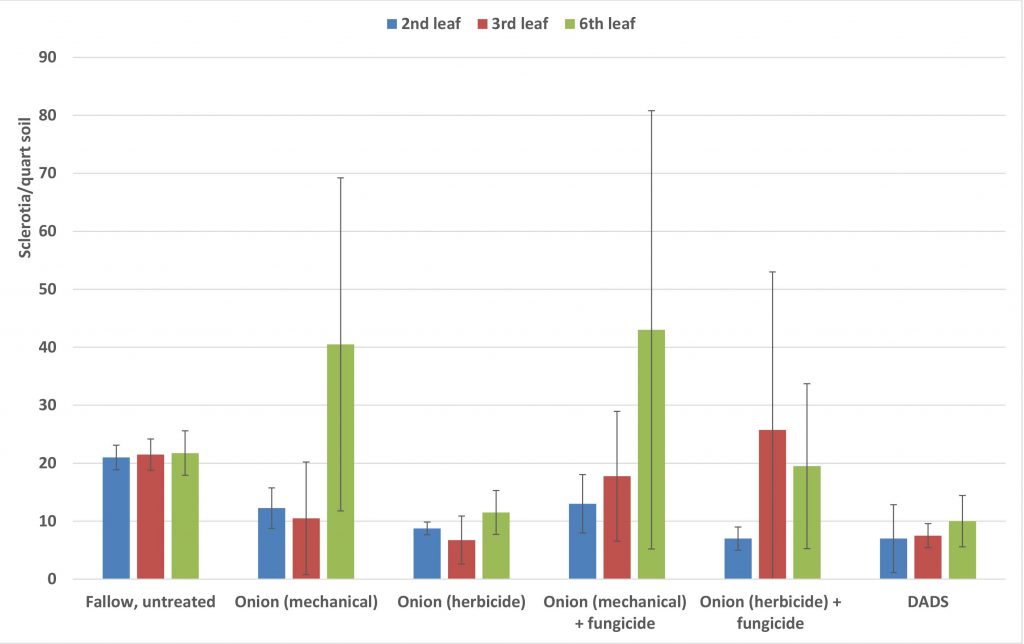

Field trials conducted in Madras, Oregon, and Tulelake, California, demonstrated that the greatest sclerotia reductions were observed when plants were terminated at the two-leaf stage. In Madras, significant reductions in sclerotia (between 38 and 67 percent) were observed, and greater reductions were observed when plants were terminated chemically as opposed to mechanically (Fig. 1). Sclerotial populations were less impacted in the Tulelake trial (24 percent reduction compared to the control), and the pathogen increased in number at the third through sixth leaf termination timings. No effect of fungicide application was observed in either field trial.

In conclusion, early termination of white, red, sweet or bunching onion as trap crops reduced populations of white rot sclerotia in infested soil, and under our experimental conditions, we observed the most consistent reductions when plants were terminated at the two-leaf stage. These findings demonstrated the potential use of Alliums as trap crops for white rot management, though the reduction in sclerotial populations in field trials was not high enough to be commercially acceptable. More research is needed to study the effects of planting density, planting date, soil type and environmental conditions before implementing trap crops in an integrated management program.

Authors’ note: This work is supported by Specialty Crop Research Initiative grant no. 2018-51181-28435 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.