|

Click to listen to this article

|

Dealing with Droughts, Water Rights and Agricultural Investment

By Molly Sears, Assistant Professor, Michigan State University

Drought is a major source of production risk in agriculture across the United States. Dry conditions can decrease planted or harvested acreage, reduce crop yields and livestock productivity, and increase expenses. Even places that usually get enough rain can face regular droughts. According to the USDA’s Economic Research Service, areas at high risk for drought experience one month of severe, extreme or exceptional drought once every two to three growing seasons. In places with less risk, drought occurs every five to six growing seasons.

When drought hits, producers deal with many challenges beyond their control, such as the weather, access to water for irrigation, and how much water the soil can hold. But producers have options: installing or improving irrigation systems, changing how to manage their land to hold more water or switching to drought-tolerant crops. While increasing irrigation is the most likely to benefit crops in the short term, producers deciding to irrigate face several challenges, such as figuring out if it’s profitable, getting access to water rights and dealing with less water during droughts.

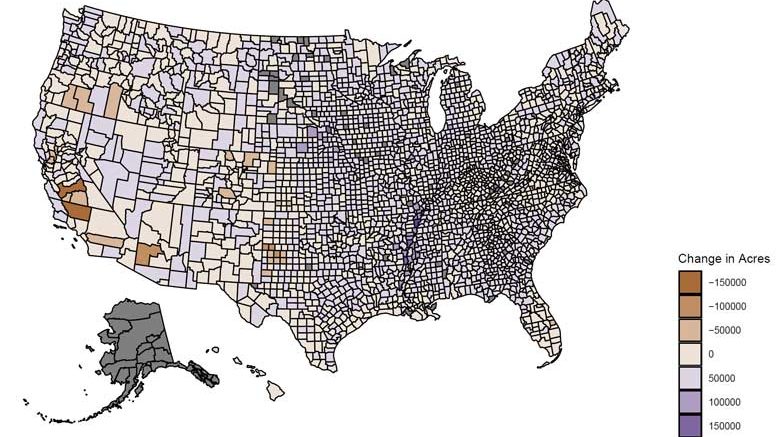

While only 20 percent of agricultural land in the United States is irrigated, 54 percent of total U.S. crop sales are from irrigated acres. The use of irrigation has increased rapidly. From 1997 to 2017, irrigated acreage increased by 1.7 million acres, reaching over 58 million acres in total. While this is good news for agricultural producers looking to reduce risk and increase crop yields, it also comes at a cost: 42 percent of U.S. freshwater withdrawals were from irrigated agriculture. As shown in Fig. 1, this change in irrigated area is not the same everywhere. Irrigated agriculture is increasing significantly in areas with plenty of water, especially in the Mississippi Delta, eastern Nebraska and the Great Lakes. While irrigation is still increasing in parts of the western U.S., other areas have seen a decline, including the Texas panhandle and California’s Central Valley.

These changes make sense because irrigation was first adopted in the West where crops needed irrigation water in order to be profitable. As irrigation equipment has gotten less expensive, the places where irrigation investment is profitable has expanded eastward. In the East, investment has rapidly occurred in areas with stable water resources and sandy soil. In the West, where the best land has mostly been irrigated already, growth has slowed down.

Another major factor in how irrigation works is water rights and how they influence a farmer’s ability to get water. In the West, most surface water is governed by prior appropriation doctrine. Prior appropriation is often referred to as “first in time, first in right.” This means that people who applied for water permits the earliest have the first priority for water. In areas where water is scarce, applying for a new water permit might not guarantee access to water. If all other users have their permits filled first, then there may not be enough water left to fill new water users’ needs.

In the eastern U.S., surface water is largely governed by riparian rights doctrine. If land is next to a body of water, that land has full access to that water. This does require coordination across all water users; no water user can use so much water that others may not have “enough” (how much is “enough” varies across states). This means that new surface water users can apply for irrigation relatively easily. However, in times of drought, riparian rights can lead to complicated negotiations that prior appropriation doctrine avoids.

As irrigation equipment becomes more efficient and less expensive, and as droughts happen more often, more farmers will want to use irrigation. From what we see now, it is likely that this growth will be faster in the eastern United States. While there are more water resources available in the East, this could lead to a need for increased coordination across agricultural producers in order to ensure that all water users have sufficient water in times of drought.