Story by Denise Keller, Editor

Photos courtesy Four Star Ag

Onion grower, packer and shipper Barry Vculek always tries to keep his finger on the pulse of the onion market. But in 2020, staying on top of – and if possible, ahead of – the market became more important than ever. When market conditions began to shift, Vculek chose to make a timely adjustment to his operation. And so far, it seems to have been the right call.

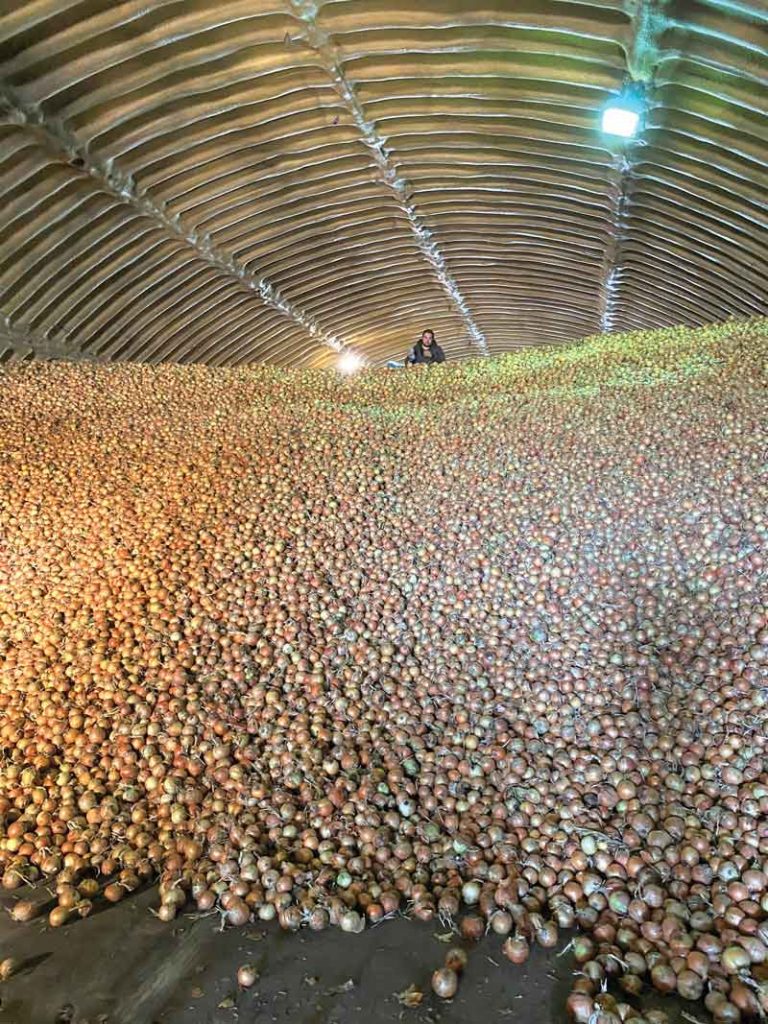

Barry and Robin Vculek own Four Star Ag in Oakes, North Dakota, where they grow onions, corn and soybeans. The 5,000-acre farm includes 1,200 acres of yellow onions. Historically, 15 percent of Vculek’s onion crop has been grown for the process market, 25 percent for retail, and 60 percent for foodservice or repacking.

But last spring, as Vculek was shipping 2019 storage onions, he began to notice the market change in response to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent shutdowns in the foodservice industry.

“I’m also sitting in the marketing chair and all of a sudden, the mediums are becoming higher priced than the jumbos, and it’s getting harder and harder to sell jumbos and easier and easier to sell mediums,” Vculek recalls. “So we had to decide do we think that’s going to continue through the full next season or is it something that’s going to phase out and be normal by harvest time in September.”

He did some quick research to understand how long the pandemic might last and found that few people felt it would be under control by the time he would be marketing the 2020 crop. Having this information prior to planting in late April, there was time to react.

He decided to change the farm’s usual planting configuration, tightening the seed population to produce a smaller size profile. The adjustment resulted in a crop consisting of about 80 percent mediums and 20 percent jumbo/colossal onions. With the increased percentage of onions sized for retail, Four Star Ag needed to double the capacity of the packing shed’s consumer line and add more space to store the additional packaged product.

“We went all in,” Vculek says. “We take production risks; we take marketing risks. This was just one more layer of risk.”

In the Market

As of late 2020, the medium price is higher than the jumbo price, Vculek says. But with only about 20 percent of the crop shipped, time will tell if he made the right decision. For now, though, it appears so.

“I’m feeling kind of proud of myself. I feel fortunate that we made that call,” the grower says. “I’d say the lesson is to follow the market or maybe even precede the market a little bit. Figure out where the market is going and try to get there.”

Although shifting onion production from the foodservice market to retail may have helped Vculek minimize the effects of the pandemic on his operation, the farm has not managed to escape the impact altogether.

The difficulty in selling the jumbos from the 2019 storage crop last spring forced Vculek to store them longer than usual and eventually destroy some of the onions.

“It’s very depressing. It really is, even if it’s just a couple of loads. You put all that money, effort and labor into growing a crop and putting it in storage and there’s still a lot of cost involved in carrying that storage all winter, and you don’t really want to give up the battle in the spring,” Vculek shares. “When you have to make the call, it’s a difficult call to make. But you have to look at the economics of it.”

The global pandemic has also affected Four Star Ag’s usage of the H-2A program. The farm employs 20 laborers from Mexico and South Africa from mid-August until June. Doing so has become more difficult, with more hoops to jump through including virus testing requirements and travel restrictions.

In the Field

In a more typical year, Vculek faces a unique set of challenges in the field. He is the only onion grower in southeastern North Dakota and one of just a few producers in the state. With limited production in the region, there has been little research conducted specific to local growing conditions. Therefore, he often takes advice from extension services in the east on disease issues and looks to the west for guidance on production practices.

He grows varieties similar to what’s grown in the Pacific Northwest, but due to a shorter growing season, yields are not as high and the window to plant is tight. Similarly, the harvest window can be fairly narrow, as well, because it can get bitterly cold in October. Winter can also be brutal, the grower says, with temperatures dipping below 0 degrees Fahrenheit.

A major upside, however, is the absence of onion thrips in the region, possibly due to the cold winter. This saves Vculek from having to treat fields for the pest, reducing input costs. He can also get away with using less fungicide than his eastern counterparts in Michigan and New York since the region is less humid.

The greatest challenge has been weed control, mainly small-seeded broadleaf weeds. However, Vculek has been working with researchers at the nearby North Dakota State University experiment station and believes they’re starting to pinpoint an effective program.

In the Industry

Farming in North Dakota is familiar territory for the Vculek family. Barry Vculek’s great-grandfather settled there in the mid- to late-1890s. Decades later, Barry’s father developed irrigation in the area and began growing dry beans and potatoes. Barry grew up on the family farm and farmed part-time while attending North Dakota State University.

In 2007, Vculek and a handful of other growers got into the onion business and were delivering onions to a packer in the area. After a year or two, Vculek was the only one wanting to continue with the crop. He purchased the packer’s equipment, started packaging his own onions and increased his farm’s acreage.

Soon after, Vculek joined the National Onion Association (NOA). Initially, the organization was a source of knowledge and meetings provided opportunities to network. As time went on, the legislative function of the NOA drew him in as he found ways to contribute.

He serves on the NOA’s legislative and environmental committees and has lobbied in Washington D.C. several times. As the only grower from North Dakota in the NOA, Vculek brings valuable connections with the state’s lawmakers. This includes Sen. John Hoeven, chairman of the Senate Agriculture Appropriations Committee, which is important for funding projects of interest to the NOA, Vculek says. Given the work done by the NOA, he is disconcerted by the number of growers not in the organization.

“The association is doing enough good things that they should be able to get a few more of those growers on board,” Vculek says. “If we can move more onions and get a better price, everybody benefits from that.”

Looking ahead, Vculek is optimistic that per capita onion consumption will continue to increase as more people are cooking at home and many consumers are being introduced to onions through the USDA Farmers to Families Food Box Program.

On his farm, he plans to continue using the production practices from 2020 to cultivate onions and widen his customer base in the retail market.