|

Click to listen to this article

|

WHAT DO BACTERIAL DISEASES LOOK LIKE? Bacterial diseases can be difficult to diagnose in onions because other problems can cause similar symptoms. It’s important to diagnose these problems accurately because management strategies might differ.

VIDEOS: The “Stop the Rot” USDA NIFA SCRI Onion Bacterial Project team produced two, easy-to-watch videos on diagnosing onion bacterial diseases. One covers foliar symptoms in the field, also called bacterial leaf blight, and the other shows bulb rot symptoms. The videos include lots of pictures and simple explanations. Each is about 4 minutes long.

Check out this video to learn how to identify foliar symptoms of bacterial diseases in the field and distinguish them from other factors (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pTYmdIwjbao). Plants with foliar symptoms do not always develop bulb rot. Similarly, bacterial bulb rot can occur without foliar symptoms.

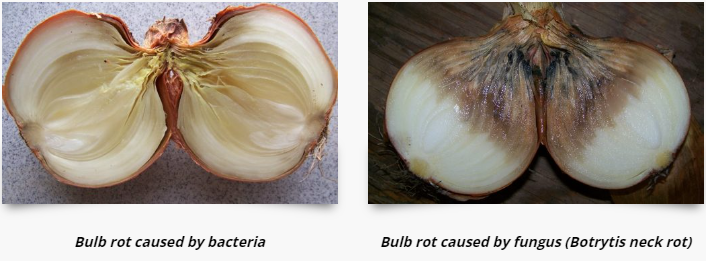

Check out this video to learn how to identify bulb rots caused by bacterial pathogens, and to distinguish these from bulb rots caused by fungal pathogens and abiotic factors (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M75sTWh8lEw&t=1s).

DIAGNOSIS: Bacterial bulb rots can be caused by many different types of bacteria (e.g., Pantoea spp., Burkholderia spp., Enterobactor spp., and more). Most cause similar symptoms, so they can’t be distinguished with a visual diagnosis. There are also fungal pathogens and abiotic factors that can cause similar symptoms. If you have rotten onions and are not sure what is causing the problem, send a sample to a diagnostic lab. Accurate diagnosis of bulb rot is important to plan an effective management strategy.

Onion growers in the Columbia Basin can contact Lindsey du Toit (dutoit@wsu.edu), Tim Waters (twaters@wsu.edu), or Carrie Wohleb (cwohleb@wsu.edu) for guidance in submitting samples for diagnosis.

DO BACTERICIDES WORK? Onion growers in the Columbia Basin should not expect to control bacterial onion rots effectively by applying bactericides to the crop during the growing season.

The “Stop the Rot” USDA NIFA SCRI Onion Bacterial Project team conducted field trials in seven states (CO, GA, NY, OR, TX, UT, WA) to investigate the use of bactericides for controlling bacterial diseases in onion. The trials in CO, OR, WA, and UT included applications of the products to both inoculated and non-inoculated plots. More than 20 products were tested. Unfortunately, none of the treatments significantly reduced bacterial bulb rot compared to the non-treated control plots, except for the trials conducted in Georgia.

Why did some bactericides work in Georgia, but nowhere else? This can be attributed, in part, to the particular species of bacterial pathogens that predominate in the different growing regions, and their differing growth habits. One of the most common bacterial pathogens of onions in Georgia is Pantoea ananatis, which causes center rot of onion. This pathogen is not as common in western regions of onion production in the USA (it’s rarely found in the Columbia Basin). P. ananatis can infect along the leaves, so foliar sprays of bactericides can come into direct contact with the bacteria. Infection by this pathogen and other bacterial pathogens of onion (such as Pantoea agglomerans, Burkholderia spp., and Enterobacter spp.) often occurs at the point of attachment of leaves to the neck of the onion plant, which makes it more difficult to get bactericides in direct contact with the infection sites in the neck, where they are protected from foliar sprays of contact (non-systemic) bactericides like copper products.

Another factor that may account for very poor efficacy of copper bactericides against bacterial diseases of onion in the Columbia Basin is that many of the bacteria isolated from onion plants in this region have been found to contain copper tolerance genes. When these bacteria were grown on agar media amended with different concentrations of copper, most proved to be highly resistant to copper. Frequent applications of copper to onion crops, as well as many other crops grown in rotation with onion, appear to have selected for bacteria with a high level of copper tolerance.

PHYTOTOXICITY: It is important to know that copper bactericides (e.g., Kocide 3000, ManKocide, Badge SC) can result in phytotoxicity symptoms when applied to onions during hot weather. The pictures above show phytotoxicity symptoms from a bactericide trial conducted in Pasco, WA in 2020 (photos by Lindsey du Toit, WSU Plant Pathology). The onions had received two applications of copper-based products during very warm weather.

SUMMARY: Bactericides are not recommended for Columbia Basin onion growers because they have not proven effective in controlling bacterial onion rots in the region, and copper bactericides can injure foliage, which can make the plants more susceptible to secondary problems, like Stemphylium leaf blight, caused by the fungus Stemphyllium vesicarium, which opportunistically infects dead and dying leaf tissues.

DOES IRRIGATION AFFECT BACTERIAL DISEASES? The “Stop the Rot” USDA NIFA SCRI Onion Bacterial Project team also conducted field trials to study the effects of irrigation practices on bacterial diseases. Here are some results…

- Drip irrigation significantly reduced the incidence of bacterial bulb rots compared to sprinkler irrigation (studies conducted in CA and GA).

- Shorter, more frequent vs. longer, less frequent irrigation under drip or sprinkler irrigation did not significantly affect bacterial bulb rot incidence (studies conducted in OR and WA).

- Timing the final sprinkler irrigation (early, normal, or late) did not affect overall yield at harvest, however ending irrigation late increased the amount of bacterial bulb rot at harvest and in storage, reducing marketable bulb yield (study conducted in central WA). Ending drip irrigation early reduced yield, but the timing of final drip irrigation did not impact bacterial bulb rot (study conducted in the Treasure Valley of OR).

- MORE FROM THE STOP THE ROT PROJECT: The “Stop the Rot” USDA NIFA SCRI Onion Bacterial Project will conclude in 2025. The original project was scheduled to end in 2023, but has been extended as team members wrap up the many aspects of the project. Summaries of the team’s findings have been presented at the PNVA Conference for several years. Click HERE to see them. You can also learn about the project by visiting their website at alliumnet.com/stop-the-rot/ or their YouTube playlist at https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLajA3BBVyv1zf2obB16bNEdQPQeLW_XB_. Watch for additional reports, papers, Frequently Asked Questions, and videos to be added to the Alliumnet website over the next year.

SOURCE: WSU ONION ALERTS